|

|

|

Reptiles (Reptilia) are members of a class of air-breathing,ectothermic (cold-blooded)

vertebrates which are characterized by skin covered in scales and orscutes.

They are tetrapods,either having four limbs or being descended from four-limbed ancestors.

Modern reptiles inhabit every continent with the exception of Antarctica.

Reptiles originated around 320-310 million years ago during the Carboniferous period,having

evolved from advanced reptile-like amphibians that became increasingly adapted to life on dry

land.

Four livingorders are typically recognized:

Crocodilia (crocodiles,gavials,caimans and alligators):

23 species

Sphenodontia (tuataras from New Zealand):

2 species

Squamata (lizards,snakes and worm lizards):

approximately 9,150 species

Squamata (lizards,snakes and worm lizards):

approximately 9,150 species

Testudines (turtles,terrapins and tortoises):

over 300 species

Aves (birds),which are not cold-blooded or scaly,are not included in this list.

Crocodiles are more closely related to birds than they are to lizards,however,so some writers who

prefer a more unified (monophyletic) grouping also include the birds:

over 10,000 species.

Unlike amphibians,reptiles do not have an aquatic larval stage.

As a rule,reptiles are oviparous (egg-laying),although certain species of squamates retain the

eggs until hatching and a few are viviparous.

Many of the viviparous species feed their fetuses through various forms of placenta analogous to

those of mammals,with some providing initial care for their hatchlings.

Extant reptiles range in size from a tiny gecko,Sphaerodactylus ariasae,which can grow up to 17 mm

(0.7 in) to the saltwater crocodile,Crocodylus porosus, which may reach 6 m (19.7 ft) in length and

weigh over 1,000 kg (2,200 lb).

The study of reptiles and amphibians is called herpetology.

Classification to order level,after Benton,2005. Series Amniota Class Synapsida Order Pelycosauria Order Therapsida Class Mammalia Class Sauropsida Subclass Anapsida Order Testudines (turtles) A series of unassigned anapsid families,corresponding to Captorhinida,Mesosauria and Procolophonomorpha Subclass Diapsida Order Araeoscelidia Order Younginiformes Infraclass Ichthyosauria Infraclass Lepidosauromorpha Superorder Sauropterygia Order Placodontia Order Nothosauroidea Order Plesiosauria Superorder Lepidosauria Order Sphenodontia (tuatara) Order Squamata (lizards & snakes) Infraclass Archosauromorpha Order Prolacertiformes Division Archosauria Subdivision Crurotarsi Superorder Crocodylomorpha Order Crocodilia Order Phytosauria Order Rauisuchia Order Rhynchosauria Subdivision Avemetatarsalia Infradivision Ornithodira Order Pterosauria Superorder Dinosauria Order Ornithischia Order Saurischia Class Aves

The origin of the reptiles lies about 320–310 million years ago,in the steaming swamps of the late Carboniferous period,when the first reptiles evolved from advanced reptiliomorphlabyrinthodonts. The oldest known animal that may have been an amniote, i.e. a primitive reptile rather than an advanced amphibian is Casineria. A series of footprints from the fossil strata of Nova Scotia,dated to 315 million years show typical reptilian toes and imprints of scales. The tracks are attributed to Hylonomus, the oldest unquestionable reptile known. It was a small,lizard-like animal, about 20 to 30 cm (8–12 in) long, with numerous sharp teeth indicating an insectivorous diet. Other examples includeWestlothiana (for the moment considered areptiliomorph amphibian rather than a trueamniote) and Paleothyris, both of similar build and presumably similar habit.

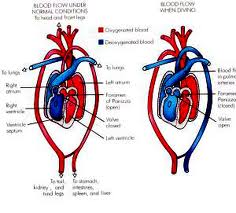

Most reptiles have a three-chambered heart consisting of two atria,one variably

partitionedventricle and two aortas that lead to the systemic circulation.

For instance,crocodilians have an anatomically four-chambered heart,but also have two systemic

aortas and are therefore capable of bypassing only their pulmonary circulation.

Also,some snake and lizard species (e.g., pythons and monitor lizards) have three-chambered hearts

that become functionally four-chambered hearts during contraction.

This is made possible by a muscular ridge that subdivides the ventricle during ventricular

diastole and completely divides it during ventricular systole.

Because of this ridge,some of these squamates are capable of producing ventricular pressure

differentials that are equivalent to those seen in mammalian and avian hearts.

Most reptiles have a three-chambered heart consisting of two atria,one variably

partitionedventricle and two aortas that lead to the systemic circulation.

For instance,crocodilians have an anatomically four-chambered heart,but also have two systemic

aortas and are therefore capable of bypassing only their pulmonary circulation.

Also,some snake and lizard species (e.g., pythons and monitor lizards) have three-chambered hearts

that become functionally four-chambered hearts during contraction.

This is made possible by a muscular ridge that subdivides the ventricle during ventricular

diastole and completely divides it during ventricular systole.

Because of this ridge,some of these squamates are capable of producing ventricular pressure

differentials that are equivalent to those seen in mammalian and avian hearts.

All reptiles exhibit some form of cold-bloodedness (i.e. some mix of poikilothermy,ectothermy, and bradymetabolism) so that they have limited physiological means of keeping the body temperature constant and often rely on external sources of heat. Due to a less stable core temperature than birds and mammals,reptilian biochemistry requires enzymes capable of maintaining efficiency over a greater range of temperatures than warm-blooded animals. The optimum body temperature range varies with species but is typically below that of warm-blooded animals; for many lizards,it falls in the 24 to 35 °C (75 to 95 °F) range,while extreme heat-adapted species like the American desert iguana Dipsosaurus dorsaliscan have optimal physiological temperatures in the mammalian range,between 35 and 40 °C (95 and 104 °F). While the optimum temperature is often encountered when the animal is active, the low basal metabolism makes body temperature drop rapidly when the animal is inactive.

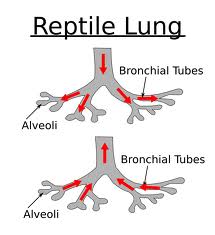

All reptiles breathe using lungs.

Aquatic turtles have developed more permeable skin and some species have modified their cloaca to

increase the area for gas exchange.

Even with these adaptations,breathing is never fully accomplished without lungs.

Lung ventilation is accomplished differently in each main reptile group.

In squamates, the lungs are ventilated almost exclusively by the axial musculature.

This is also the same musculature that is used during locomotion.

All reptiles breathe using lungs.

Aquatic turtles have developed more permeable skin and some species have modified their cloaca to

increase the area for gas exchange.

Even with these adaptations,breathing is never fully accomplished without lungs.

Lung ventilation is accomplished differently in each main reptile group.

In squamates, the lungs are ventilated almost exclusively by the axial musculature.

This is also the same musculature that is used during locomotion.

Most turtle shells are rigid and do not allow for the type of expansion and contraction that other

amniotes use to ventilate their lungs.

Some turtles such as the Indian flapshell (Lissemys punctata) have a sheet of muscle that envelops

the lungs.

When it contracts, the turtle can exhale.

When at rest,the turtle can retract the limbs into the body cavity and force air out of the

lungs.

When the turtle protracts its limbs,the pressure inside the lungs is reduced and the turtle can

suck air in.

Most reptiles lack a secondary palate,meaning that they must hold their breath while swallowing. Crocodilians have evolved a bony secondary palate that allows them to continue breathing while remaining submerged (and protect their brains against damage by struggling prey). Skinks (family Scincidae) also have evolved a bony secondary palate,to varying degrees. Snakes took a different approach and extended their trachea instead. Their tracheal extension sticks out like a fleshy straw and allows these animals to swallow large prey without suffering from asphyxiation.

Reptilian skin is covered in a horny epidermis,making it watertight and enabling reptiles to live on dry land, in contrast to amphibians. Compared to mammalian skin,that of reptiles is rather thin and lacks the thick dermal layer that produces leather in mammals. Exposed parts of reptiles are protected by scales or scutes,sometimes with a bony base,forming armor. The scales found in turtles and crocodiles are of dermal,rather than epidermal,origin and are properly termed scutes. In turtles,the body is hidden inside a hard shell composed of fused scutes.

Excretion is performed mainly by two small kidneys. In diapsids,uric acid is the main nitrogenous waste product;turtles, like mammals,excrete mainly urea. Unlike the kidneys of mammals and birds,reptile kidneys are unable to produce liquid urine more concentrated than their body fluid.

Most reptiles are carnivorous and have rather simple and comparatively short digestive tracts,meat being fairly simple to break down and digest. Digestion is slower than in mammals,reflecting their lower resting metabolism and their inability to divide and masticate their food.

Camouflage Alternative Defence In Snakes Defence In Crocodiles Shedding & Regenerating Tails